DO WE BELONG IN THE MIDDLE EAST? THE ISRAELIS MAKING THE LEVANT RELEVANT AGAIN

Do We Belong in the Middle East? The Israelis Making the Levant Relevant Again

Also this week, a young woman loses her grandfather in Gaza – and sings about him. Also, the Tel Aviv Cinematheque explores blaxploitation, Shadi Mar'i wins big at the Jerusalem Film Festival, and why a man chainsawed his grandfather's paintings

July 26th, 23PM July 26th, 23PMAshkenazi, Mizrahi, Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Israeli, European, Palestinian, Arab. Certain words that define our identities and highlight social struggles have become commonplace in everyday Israeli conversations. The term Levantinism, however, never belonged on that list.

It's not complicated to see why: This vague word is often charged with negative, demeaning connotations going back to French and British colonial times. People from the West dubbed the Middle East the Levant (based on the Latin word levare, meaning rising, referring to the sun rising in the east).

"Levantinism" was then used to refer to the people of the region in a degrading way; it was also a term for those who don't really belong anywhere, who exist between places and cultures and may assume the cultures of others.

Another explanation for the term's low popularity is that Israelis prefer to turn their backs on their geographic and cultural surroundings. They live in a country completely sealed off from those surroundings, while they also avoid the fluidity of their own personal and national identities.

Yet in recent years, along with a growing discussion about our future as a state embedded in a region that is both foreign and familiar, Levantinism is rising again. In 2019, the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv dedicated an exhibition to Jewish novelist and essayist Jacqueline Kahanoff, who died in 1979 in Tel Aviv. She was the most influential writer on the subject.

Then in 2022, historian David Ohana published two Hebrew-language books on Kahanoff: an autobiography and a collection of her writings called "Jacqueline Kahanoff: We Are All Children of the Levant." And last year, the Beit Avi Chai cultural center in Jerusalem dedicated a podcast to the Cairo-born writer, "From East the Sun: Jacqueline Kahanoff."

Now, this month, two books on Levantinism are coming out in Hebrew: "In Favor of Levantism: An Essay and Thirteen Conversations" by literature researcher Idan Zivoni (Resling Press), and "Bring the Sun In: Levantine Perspectives," edited by historians and writers Liat Arlette Sides and Ketzia Alon (Gama Press). On Thursday, the Jaffa theater held an event with the writers to discuss their projects.

Why is Levantinism so relevant now? Even though work on both books lasted several years, the fact that they're coming out now, after October 7 and during the Gaza war, is crucial.

"Levantinism is exactly about the embarrassment and discomfort of not being here or there, of that identity confusion. Post October 7 this is very relevant," says Zivoni, who is also the editor of Resling Press.

"On the one hand, we feel unwanted in our region; it's rejecting us as an occupying, Jewish country. And of course nobody is exactly waiting for us in Europe to move back. That in-between space is a very Israeli experience. I'm not sure an Egyptian from Cairo feels unwelcome in their surroundings, I don't think Palestinians feel that this region rejects them; rather, it's that they're being repressed by us."

Each year on October 24 for the last decade, Alon, Arlette Sides and other Kahanoff fans visit her grave. They hold a small ceremony and read from her books. They last went there during the first month of the war and found themselves the only people at the cemetery. Suddenly sirens wailed and they could see missiles fly by.

"We lay on the ground between the silent tombstones next to her grave, waiting for shrapnel to fall," Arlette Sides writes in the book. Then they went back to reading. "It felt like the ghost of the writer was hovering above us, coming back from the dead, responding to current events and referring to texts she wrote way back in the '60s, as if more than half a century hadn't gone by," Arlette Sides writes.

Alon, a self-proclaimed Kahanoff fan ("I have a big painting of her drawn by Ronny Someck above my desk") explains that Kahanoff understood what our "prime ministers, generals and ministers still fail to see. We need to teach Arabic from a young age, we need to completely change our attitude toward the Arab world, we need to understand that we're now part of it, to maintain a discourse that isn't so insanely racist but rather loving and connecting, that knows the intellectual treasures that Islam has to offer us."

As she puts it, "Reading Kahanoff now, you see how far she saw in advance and was a modern prophet. It's incredible to read her. She came to Israel in the '50s and could see through the way Israel integrates into this region, its sovereign rule."

Arlette Sides' and Alon's book includes texts on Levantine aesthetics and identities in Egyptian cinema, a translation of an Egyptian play written by a Jewish playwright, Mizrahi literature between hybridity and struggle, an essay by the late Shulamith Hareven called "I Am a Levantine," and a piece by Yossi Yonah reflecting on the importance of Levantinism after October 7.

Zivoni's second nonfiction book started as an essay he wrote three years ago during the fighting with Gaza in May 2021; it swelled into 150 pages of ideas. "The big drama was the explosion between two communities, the Arab and the Jewish in Israel, with violent clashes inside the Green Line," he says.

"That was the trigger for me to write, an attempt to see how we can turn the relations from realms of enemies into realms of neighbors. And that includes the Syrians, the Jordanians and the Lebanese. To talk and find cultural similarities."

He adds: "When Levantinism was recharged with a positive meaning in the 20th century, you had a group of intellectuals – Jewish and also Arabs – who realized that they were from the East but looked to the West, which is very much connected to the action of colonialism, which doesn't only trample, but also discriminates culturally. A privileged Jewish minority was discriminated against but also became part of the colonial legacy.

"Kahanoff felt that she had a second home in Paris, so she realized that she was living a double life – in the East but in a dialogue with the West, a mutual relationship. She didn't only feed on the West, the West was also interested in her, the greater her."

A young woman loses her grandfather in Gaza

This week, after the army announced that Israeli hostages Alex Dancyg, 76, and Yagev Buchshtab, 34, were killed several months ago in Gaza, Dancyg's 18-year-old granddaughter, Talya Danzig, posted a video on social media criticizing the Israeli government's actions and failure to bring the hostages back home. On the back of Danzig's raw and authentic emotions, the post went viral.

Danzig is also a novice singer with a unique soft voice. Six months ago she released a song about her grandfather in captivity, "The War Dragon."

She is currently working on new material. This week, producer Dan Hirsch wrote online that after a recording session, Danzig told him about a new song she wrote about her grandfather, "I Have Power." He filmed her performing it and shared it with his followers.

You can find it all at

the Cinematheque

At this point it almost feels like the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, which last month celebrated its 50th birthday, is creating programs solely to allure Tel Aviv resident Quentin Tarantino to come visit. Last year the American director showed up at a screening of one of his favorite giallo films, those Italian horror movies that were big in the '60s and '70s. The Cinematheque was putting on a whole giallo retrospective.

Next month, the institute is offering a special program dedicated to the best blaxploitation films. The movies will include "Foxy Brown," "Across 110th Street," "Shaft," "Coffy" and "Black Caesar." Will viewers care enough to make the connection with other ethnic minorities' struggles that are happening right under their nose?

Actor Shadi Mar'i shines

The big winner of the Jerusalem Film Festival is Bedouin director Yousef Abo Madegem's debut feature "Eid" about a young Bedouin man who struggles through a forced marriage and his past as a victim of sexual assault. The movie, which is considered the first full-length Bedouin feature film, won the Haggiag Award for best Israeli feature. Its star, the great talent Shadi Mar'i known from his role in "Fauda," won the Anat Pirchi Award for best actor.

According to the judges, Mar'i won "for a completely convincing portrayal of the main character, all his conflicting emotions, along with a sensitive understanding of his defiance, pain, and hope."

Actress Lia Elalouf won the Anat Pirchi Award for best actress for Tom Nesher's "Come Closer." Nesher also won the GWFF Award for best Israeli first feature, and Maya Kenig took the Anat Pirchi Award for best screenplay for "The Milky Way."

Shakked Auerbach, who was interviewed by Haaretz's Adrian Hennigan this month, won the Diamond Award for best director of a documentary for "Strange Birds." The judges wrote: "A very moving account of the struggle of a family with an autistic son or brother from the point of view of his younger sister. Through its remarkable editing, fine use of music, and family archives, the film invites us into a story of love and care. Life is hard, but love makes it beautiful."

The Diamond Award for best Israeli documentary went to "The Governor" directed by Danel El-Peleg. In the Israeli Video Art & Experimental Film Competition, "I'm Not Afraid of the Apocalypse, I Am Afraid You Don't Love Me Anymore" by Leila Erdman-Tabukashvili won the Lia van Leer Award, Courtesy of Rivka Saker, while "Little Boney and His Winter Extinguisher (at Last!)" by Jonathan Omer Mizrahi won the Ostrovsky Family Fund Award.

Grandson chainsawed his paintings

Pinchas Litvinovsky was once considered one of Israel's best painters. He was known for his beautiful portraits, especially those of Israeli leaders. When he won the Israel Prize in 1980, the judges called him "a pioneer of Israeli painting and a founder of modern Israeli art."

Moshe Dayan even gifted him a house in Jerusalem's Katamon neighborhood, where he lived and painted. Twenty-five years ago, some of his paintings were sold for $100,000 each. But since then a lot has changed.

Litvinovsky's house was never turned into a museum as was once planned, and a few years ago the Jerusalem municipality claimed that the city owned the property. So it ordered his grandson, a man in his 70s, to empty the house of all the artist's paintings.

After a long period of resistance, the grandson, who didn't manage to interest any art institution in the works, started moving paintings out of the house. But having no place to store them, he destroyed thousands of them over a few months. For some he used a chainsaw, others he dissolved in his bathtub. Of 6,000 paintings, only hundreds survived.

The best of the survivors can now be seen at the new exhibition "You Must Choose Life: That Is Art" at Beit Avi Chai, curated by Amichai Chasson. The exhibition "aims to highlight the best of the remaining pieces, showcasing various playful, both sensual and spiritual artistic facets of Pinchas Litvinovsky's legacy."

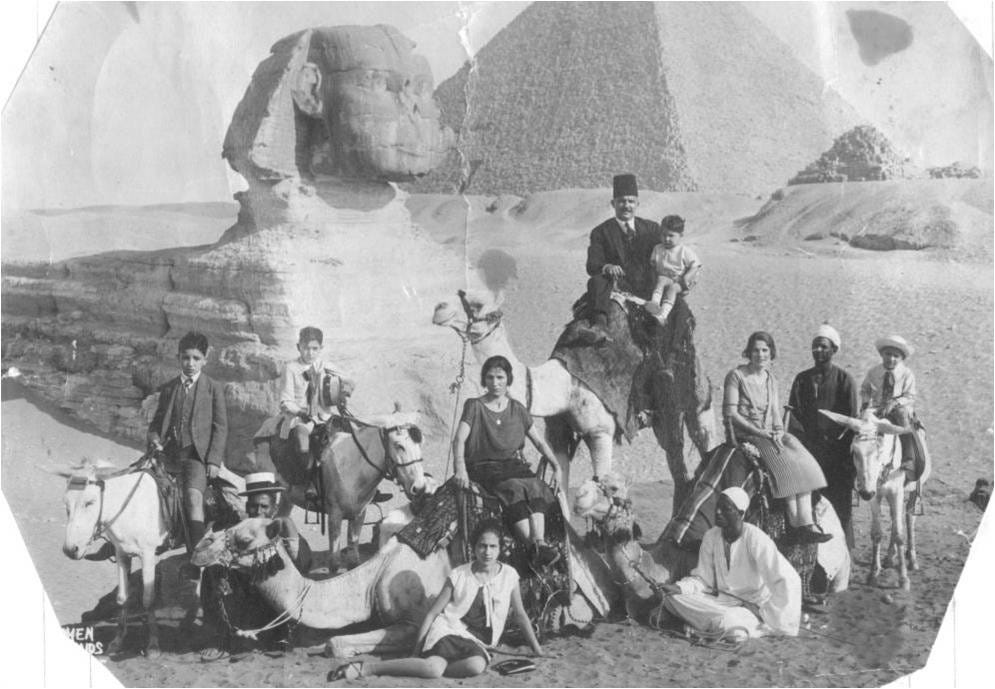

Beside portraits, Litvinovsky, who was born in Ukraine when it was part of the Soviet Union, was also interested in the new landscapes in Israel. According to the exhibition, "like many artists of the time (such as Reuven Rubin, Nachum Gutman, Arieh Lubin and others), Litvinovsky portrayed the daily life he saw in the Galilee and the Judean Mountains with a degree of naivety verging on Orientalism."

This included Arabs in kaffiyehs, Hasidic Jews in shtreimels, Yemenite Jews with sidelocks, women in veils or snoods, "as well as local farm animals such as donkeys and camels."

2024-07-26T20:45:39Z dg43tfdfdgfd